This year, our Advent series at Park Church is called Echoes of a Voice. If you’ve seen the photography in the building, on the livestream, on Instagram, or in your Advent Guide, you’ve probably asked yourself, “what is this about?” or “what’s the connection?”

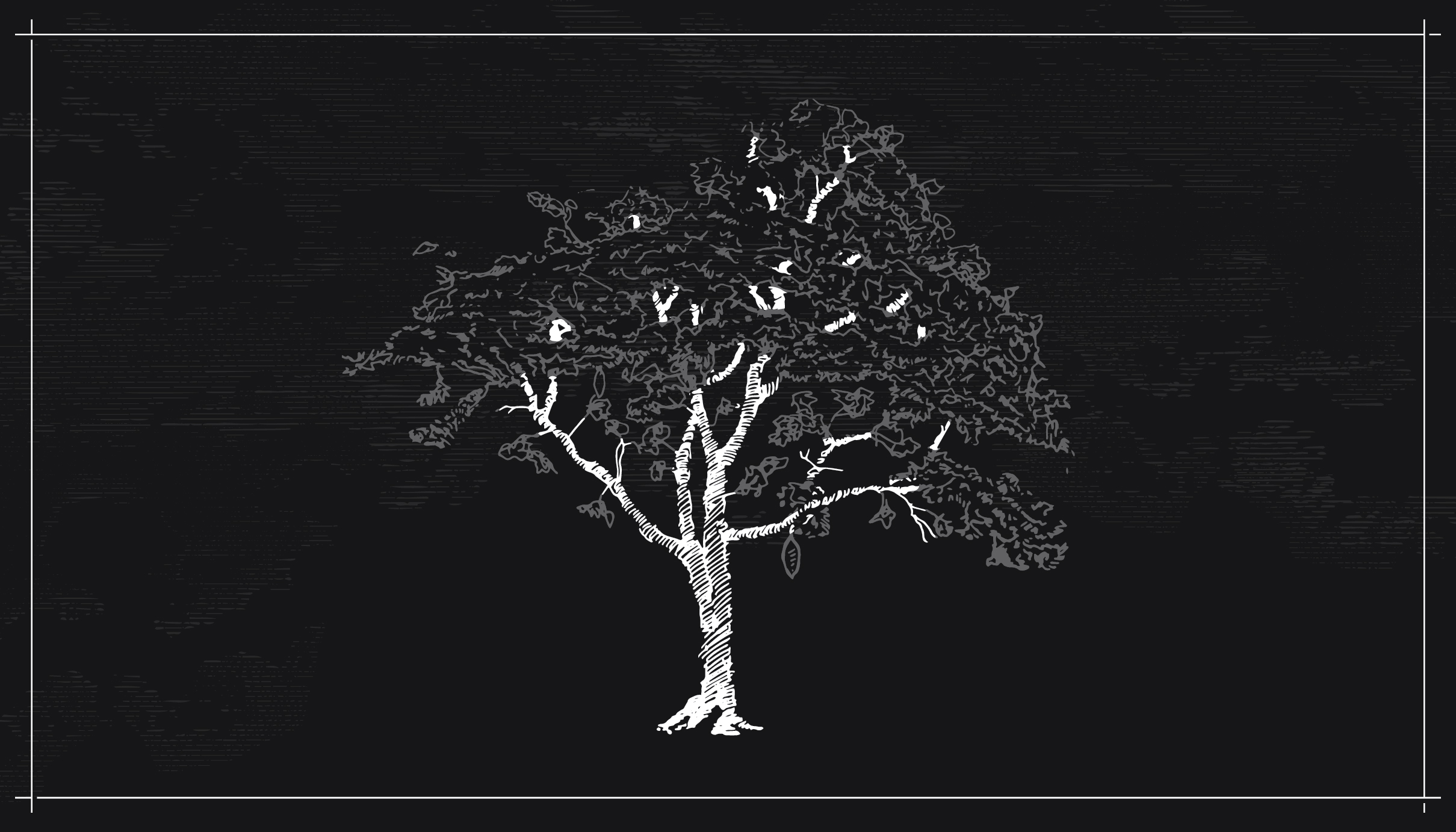

First, we want to introduce you to John Forney. John and his family have been at Park Church for several years. He’s a self-taught black and white film photographer, working with vintage 8×10 cameras in large and medium formats. For Christ in the Psalms 2020, John shared an incredible photograph in support of our Psalm 104 week. After digging deeper into his work, we reached out about John’s What Remains? series as an artistic vision for Echoes of a Voice.

First, John is going to tell the story of What Remains? Next, we’ll share about its connection to Advent this year at Park Church.

What Remains?

by John Forney

I began this project about 17 years ago as a novice photographer without any real experience. I was looking for an approach to combine my outdoor interests and my photography interests in a way that wouldn’t necessarily create more “landscape photography.” I was mostly aware of what I didn’t want (traditional landscapes), but I thought maybe ghost towns could provide an opportunity to explore and work out some sort of photographic vision.

At first, I started to explore ghost towns along the front range. They were nearby, accessible, and allowed me to get my bearings. What may not be as obvious from the early images in the series is that I was shooting at night. It was the only free time I had. I could ballpark my exposure times and let the camera record light for quite some time. Minutes turned to hours. Long exposures uniquely record time and space in ways we don’t experience. I was hooked.

At first, I started to explore ghost towns along the front range. They were nearby, accessible, and allowed me to get my bearings. What may not be as obvious from the early images in the series is that I was shooting at night. It was the only free time I had. I could ballpark my exposure times and let the camera record light for quite some time. Minutes turned to hours. Long exposures uniquely record time and space in ways we don’t experience. I was hooked.

I slowly started to amass a small body of work. The collection of images started to seem cohesive―my loose definition of a project. At this point it was simply personal amusement, but not for long.

I had two experiences that were pivotal in shaping my understanding of the project:

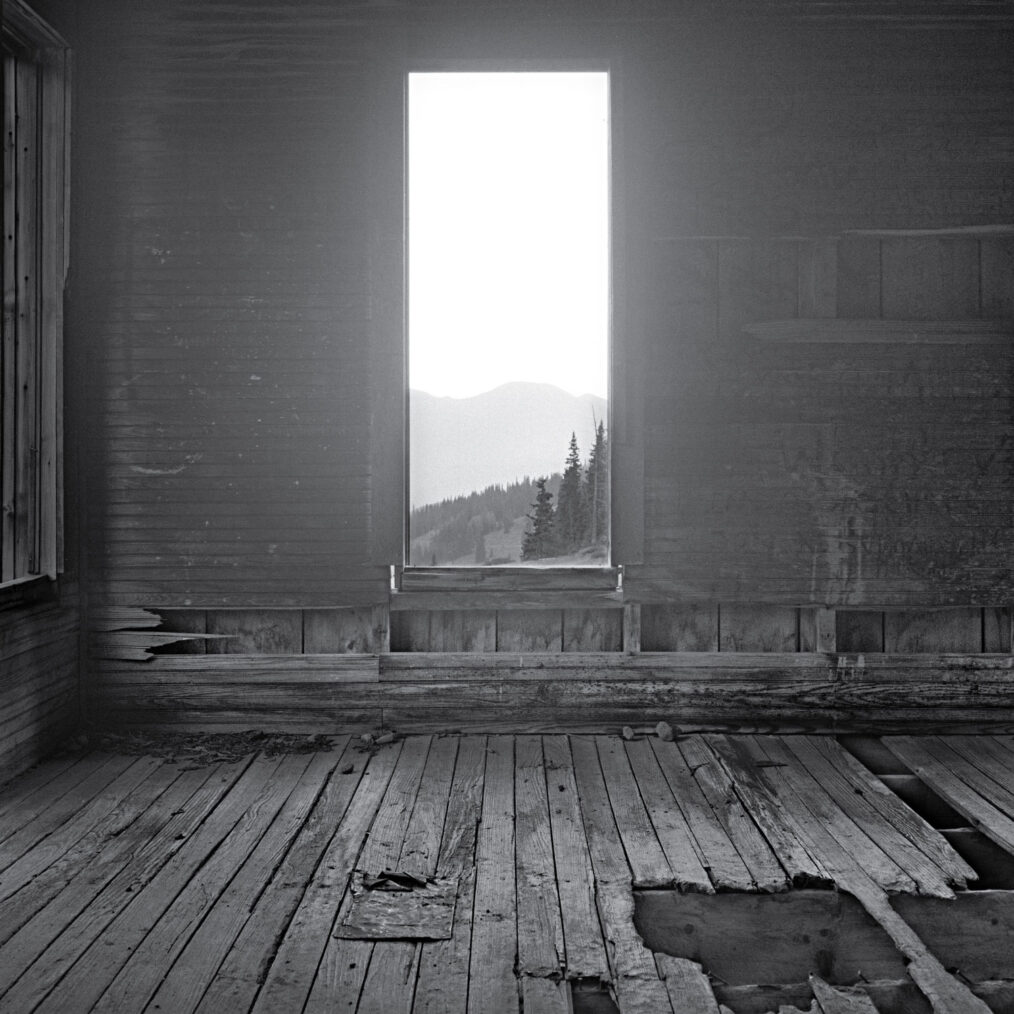

The first experience was on wintery January day. I had obtained permission to enter the abandoned Paris Mill near Alma. What little research I had on the mill indicated it had an unusually large amount of original mining machinery―and, that it was literally infested with rats. I signed a waiver with the real estate company representing the mill releasing them from any personal liability on my part and on a snowy, January day I entered the mill.

Now, my wife can tell you how unnerved I am just about mice. Frankly, they freak me out. Yet I had willingly stepped into a rat-infested mill. As a matter of personal safety, I’d never say I felt at ease, but as minutes became hours I slowly worked my way through the mill making images. Certain areas of the mill were very dark as the roof and walls were still intact. Other areas where the roof had collapsed became large labyrinths of light reflecting off structures, machinery and the snowfall. In one sense, I didn’t want to leave. In another sense, I couldn’t wait to be done.

Now, my wife can tell you how unnerved I am just about mice. Frankly, they freak me out. Yet I had willingly stepped into a rat-infested mill. As a matter of personal safety, I’d never say I felt at ease, but as minutes became hours I slowly worked my way through the mill making images. Certain areas of the mill were very dark as the roof and walls were still intact. Other areas where the roof had collapsed became large labyrinths of light reflecting off structures, machinery and the snowfall. In one sense, I didn’t want to leave. In another sense, I couldn’t wait to be done.

This first experience at Paris Mill set the metaphorical backdrop for the next chapter in my life.

The second experience occurred in a much less “assuming” manner. It was a Saturday morning. I was at home. I was washing dishes. My three then-young kids were doing who knows what—washing the dishes was a momentary solitude from the busyness of parenting. My mind was wandering, thinking about my ghost town project. Like a lightning bolt, an epiphany, maybe even a warning: I had the most vivid impression. All I heard or saw in my mind was “THIS IS YOU! You are the ghost town.”

I was taken aback. Like what? But very quickly I kind-of understood. Despite how it sounds on paper, I didn’t perceive this as condemning. It was something deeper that was very personal to me after experiencing ghost towns. I was, unknowingly, on the verge of a very dark season in my life. This time, instead of willingly walking into the “mill,” I would be thrown in. The horrors would exceed my deepest fears. In many ways, this message was one of encouragement that I would inevitably need: “Above all else, guard your heart, for it is the wellspring of life.”

It was soon after this second experience that I named this project What Remains? The title has some obvious tie-ins with the subject matter. But the deeper meaning begs the question: “How’s your heart?”

As I look back on this project, I have realized how fear provides an invitation and an opportunity. As I fearfully stepped into the Paris Mill years ago, I realized how addressing fear provides both and invitation and an opportunity to grow. Looking back, my fears were clear and present. But the opportunity provided me with a huge resilience to do the work that I felt convicted to do and produced some of my favorite images to date.

As I look back on this project, I have realized how fear provides an invitation and an opportunity. As I fearfully stepped into the Paris Mill years ago, I realized how addressing fear provides both and invitation and an opportunity to grow. Looking back, my fears were clear and present. But the opportunity provided me with a huge resilience to do the work that I felt convicted to do and produced some of my favorite images to date.

“For now we see in a mirror, dimly…” At that time, I could not know the circumstances and fears that would ensue in the years to follow. These are fears that only with God-given faith, can I walk into and through. I am still in this dark “mill” ―but not alone.

“but then face to face.” I believe He will one day, face to face, reveal the beauty only He can create through His redemption in ways I could otherwise never have known so personally.

See the complete series here. To see more of John’s work, visit johnforney.com

Advent is a season of twofold longing. First, we remember the longing of the world for the first coming of Jesus, the long-foretold Messiah who brought an easy yoke of gracious salvation and love to a weary world. Second, we look at our own world and long for its renewal at Jesus’ second coming. Things are not right here, but we can hear the Redeemer’s voice echoing everywhere. In particular, we can hear His voice in our core longings as a culture and as individuals—we long for justice, we hunger for relationships, we quest for spirituality, and we delight in beauty. None of these longings are fulfilled outside of Christ.

In John Forney’s What Remains? series, we see things and places and moments of transcendent beauty, all framed by brokenness and abandonment. These images speak both to haunting and to unspeakable beauty.

As John explained above, we now see “in a mirror, dimly.” We hear His voice glance off the mighty rocks and whisper across the confusing, empty expanses. In our brokenness, in our longing, and in our best efforts, we know all the better of the great glory beyond us. The Lord Jesus is the fulfillment of these longings, the antidote to our belligerent works-righteousness, and the kingdom of light and wholeness that we dream of on the tired earth.

As the weeks of Advent Progress, we’ll explain each individual piece here on our blog, sharing the images on Instagram. Here are direct links to the week’s we’ve covered so far:

Week One: Justice and the Cave Trail

Week Two: Relationships and the Old Tram

Week Three: Spirituality and the Mine Wall

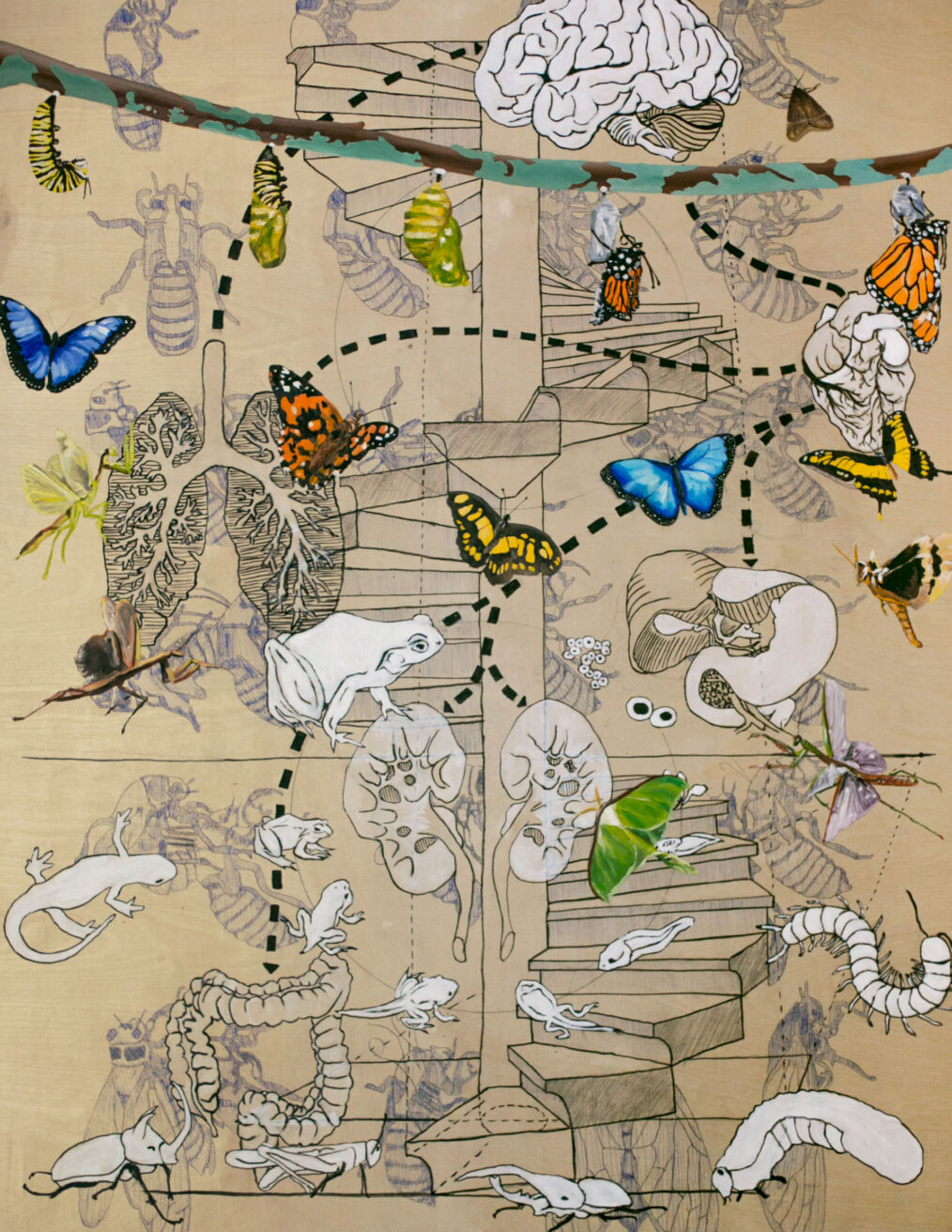

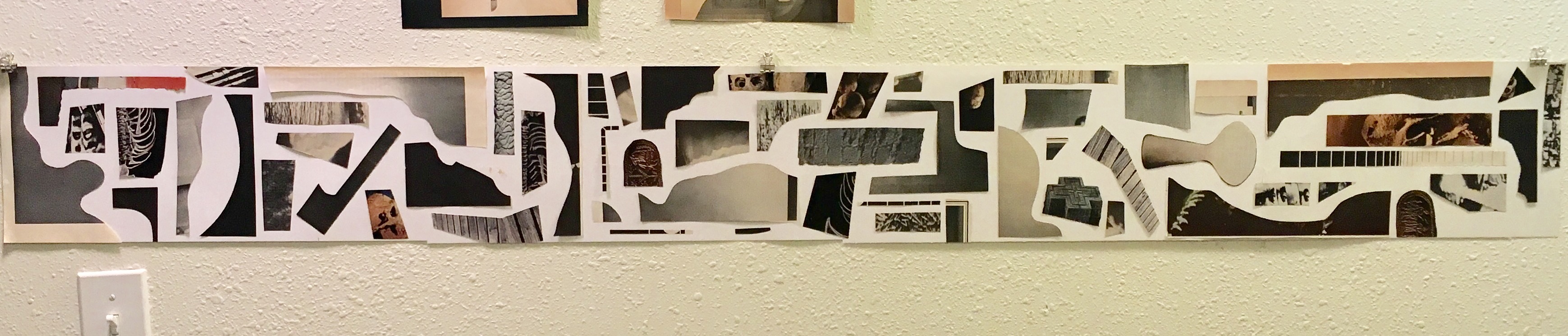

In another early concept, I envisioned cracks and a shattered pattern getting less and less cracked -the color getting brighter and brighter as the collage progressed. U;timately, I felt like it was—again—less robust of an idea, and cracks don’t really “heal themselves.” It’s difficult to express that idea, even though I liked the graphic potential of it.

In another early concept, I envisioned cracks and a shattered pattern getting less and less cracked -the color getting brighter and brighter as the collage progressed. U;timately, I felt like it was—again—less robust of an idea, and cracks don’t really “heal themselves.” It’s difficult to express that idea, even though I liked the graphic potential of it.

Lastly, an image of the final collage in-process, before I added the pink squares. The squares sort of came to symbolize markers in the passage of time, little ebeneezers if you will.

Lastly, an image of the final collage in-process, before I added the pink squares. The squares sort of came to symbolize markers in the passage of time, little ebeneezers if you will.